Can we understand war through video games? The Imperial War Museum’s ‘War Games’ exhibition

by Christina Chester on Apr 20, 2023

Over the past few decades, video games have become one of the most successful and popular forms of entertainment. With over two billion gamers worldwide, scholars have advocated for more research on how representations of past events in video games contribute to our broader cultural understandings. One of the most popular genres is that of war games: where digitally representing a real-life war is the basis of both gameplay and narrative. The Imperial War Museum’s new exhibition, ‘War Games’, provides insight into how they are created and what impact these historical representations of warfare can have on users. I think it is a missed opportunity. Continue reading to learn why.

Our world has been shaped by the violence and destruction of real war. But in video games, war and conflict are backdrops for gameplay. Games have the power to affect the way we remember and feel about conflict.’ - IWM.

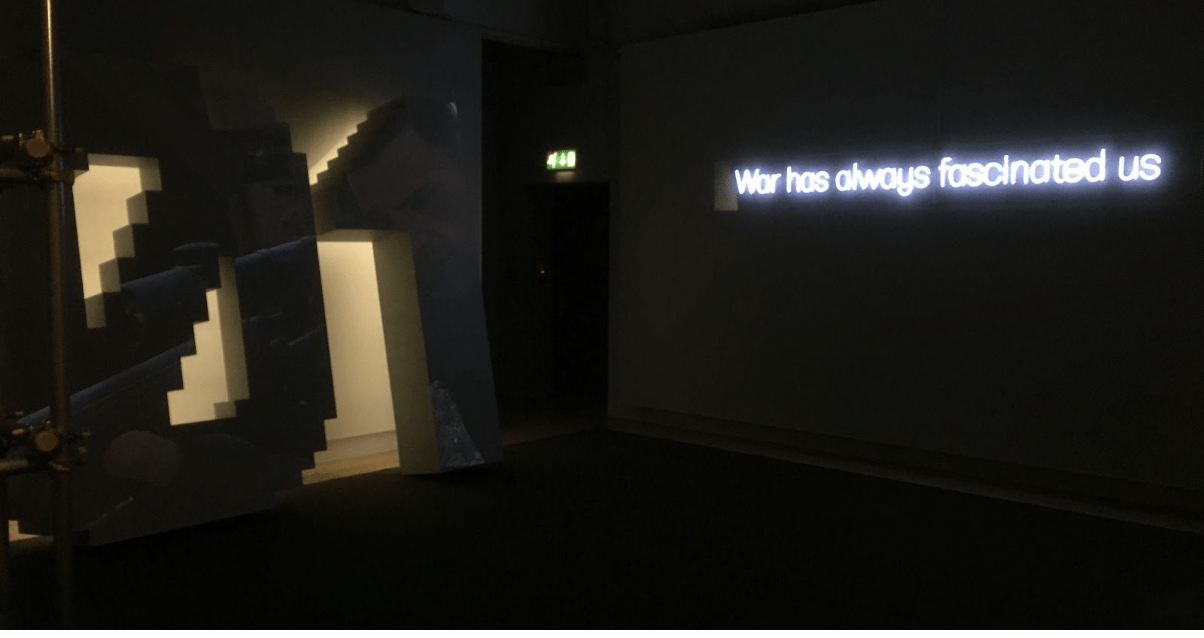

The exhibition is divided into nine ‘Levels’, each introducing a new topic. ‘Level 01’ features a large ‘01’-shaped screen displaying game footage. The words, ‘War has always fascinated us’, are illuminated on the wall of the dark room, preparing the museum-goer for ‘Level 02’, featuring the history of the ‘war game’ concept. Displayed board games, such as ‘Battleships’, demonstrate how video games are merely a new, digital form of a long-standing tradition in which the ‘act of play’ is utilised to recreate war scenarios. Placards explain how these manufactured situations have historically been used for both entertainment and strategic purposes.

‘Level 01’: ‘War has always fascinated us’, illuminates an otherwise darkened room.

This would have been an excellent section to discuss the highly popular war strategy and civilization games, such as Civilisation and Age of Empires. Despite the historical inaccuracies that are often found within these games, scholars such as Rolfe Daus Peterson have found that such games are nonetheless helpful in broadening the gamers’ understanding of the factors that have shaped military conquest in history. Unfortunately, this opportunity was missed, as the section instead focuses predominantly on overviewing the genre’s brief history.

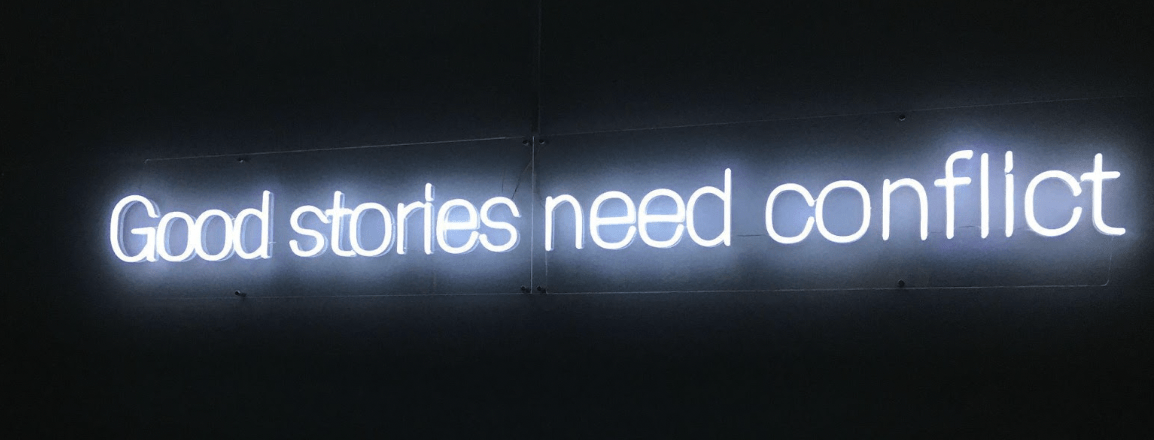

‘Level 03’: ‘Good stories need conflict’, illuminated on the wall opposite the screening of interviews.

Similarly, the ideas presented in ‘Level 03’ could have been much expanded upon. A large, pixelated screen shows a series of interviews by historians, psychologists, and gamers. The virtual panel of speakers answers questions about why war is such a fascinating phenomenon and what makes gaming an enjoyable pastime. Some of these answers were informative and interesting as they explained how video games can provoke specific emotions and thoughts. However, discussions around the possibility of interactivity triggering intense feelings of guilt and betrayal within gamers failed to delve deeper into how these emotions may impact the overall understanding of past wars or what lasting impressions (and possible misconceptions) the gamers may subconsciously absorb.

Some of the exhibition’s most interesting displays (Levels 06 - 08) partly touch on how video games can shape and inform our understanding of war history. In ‘Level 06’, the museum-goer is introduced to two games that aim to illuminate previously neglected narratives within this genre: Through the Darkest of Times and Six Days in Fallujah. In Through the Darkest of Times, the player can join a civil resistance group during Nazi-era Berlin. The player forms a part of the narrative, ‘witnessing’ and experiencing the stakes, challenges and terror that civilian resistant fighters faced in opposition to the Third Reich.

In Six Days in Fallujah, the player is a US marine fighting for control over the Iraqi city of Fallujah in 2004. They have to navigate the terror and uncertainty of house-to-house urban conflict whilst coming into contact with terrified civilians.

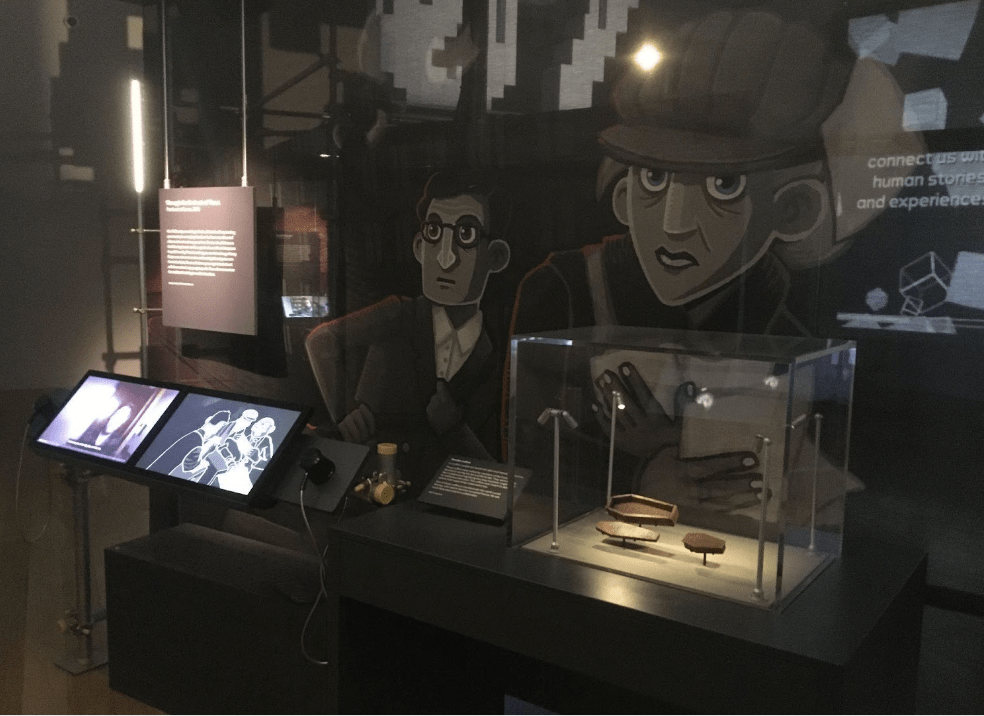

A real-life artefact associated with the wars these games cover is laid next to a screening showing interviews with the creators. Both games aim to widen the player’s perspective on these wars' lived experiences, especially of civilians and soldiers. The decision to marry an actual material artefact with a digitalised explanation emphasises the real lived experiences in war that are now forming a part of a digital heritage, albeit in a game format.

‘Level 06’: Through the Darkest of Times, Paintbucket Games, (2019).

The interviews with the creators of the games are particularly insightful, as both discuss the importance of historical exploration and heritage in video games. Jörg Friedrich explained that historical accuracy was imperative when creating Through the Darkest of Times. He argues that since popular culture confirms our understanding of history and most people learn from media, interactive games that involve history need to reflect the complexity and lived experiences of the given periods. Friedrich also believes that video games present the opportunity to engage people with history uniquely, thanks to the interactivity the player is provided with.

Likewise, the creative director of Six Days in Fallujah, Jamie Griesemer, believes that the real-life experiences of marine soldiers can be conveyed in a more complex and empathetic way through interactivity. He explains the extensive process in which over a hundred US marines, veterans and surviving citizens from Fallujah were interviewed to recreate an authentic representation of this chapter in the Iraq War. In doing so, Griesemer aimed to present the player with the questions and trade-offs the actual soldiers would have had to have faced in order to give a more in-depth understanding of these war experiences. Both Through the Darkest of Times and Six Days in Fallujah are prime examples of game developers' initiatives to provide a more nuanced historical representation of war to its players.

However, as complex and thought-provoking as the games featured in ‘Levels 06-08’ may be, most of these games fall into the ‘Indie’ category. Indie games are created by independent developers, who usually lack funding from larger publishers. Although the Indie game sector is steadily growing, it remains a niche. Over 50% of the Indie games on the popular game distribution service, Steam, have earned less than $4,000 in sales, for example, whereas AAA war games, such as Call of Duty: Black Ops, sell tens of millions of copies.

What this ultimately means is that First Person Shooter (FPS) games, in which history is usually boiled down to military action alone, are the games that are mainly consumed. These war games, which portray more simplistic historical metanarratives, are the ones that have the most exposure and, therefore, the most potential to shape historical understanding and heritagisation within popular culture.

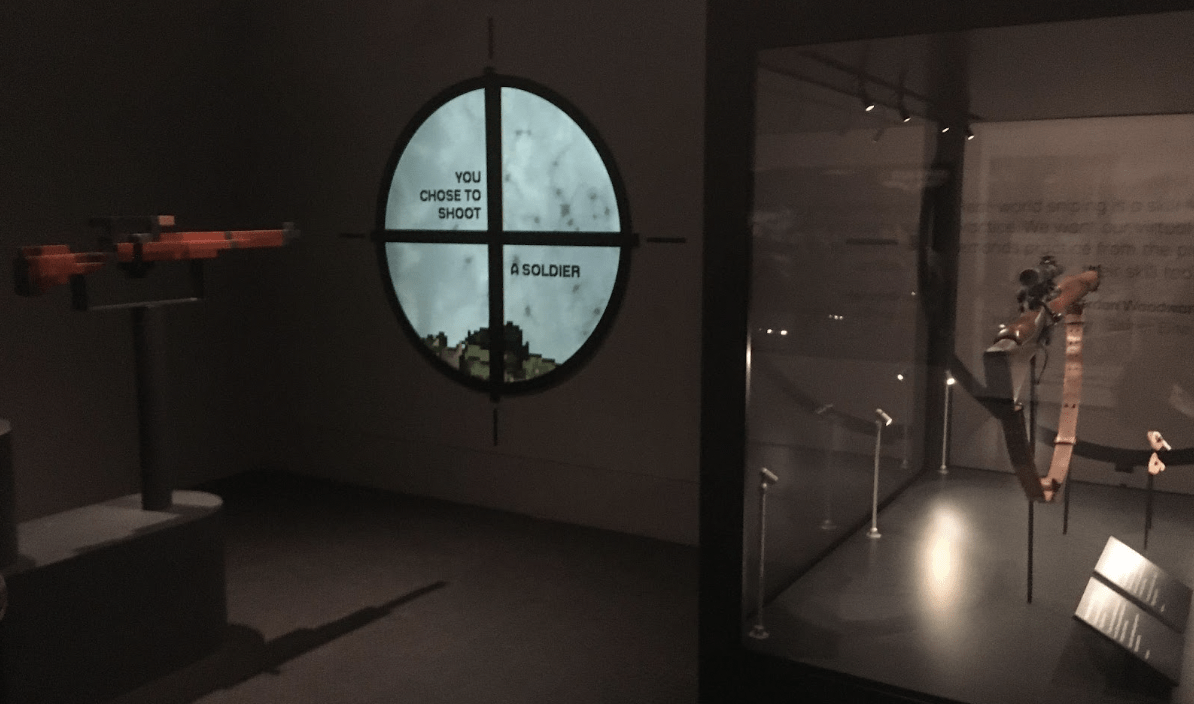

‘Level 05’: An interactive display invites the museum-goer to ‘shoot’ virtual targets that appear on screen in their line of fire. ‘Citizens’, ‘soldiers’, ‘dogs’ and even ‘robots’ appear on the screen.

Given that FPS games are one of the most popular types within the genre, it is unfortunate that the exhibition does not adequately explore how many of these negatively reaffirm harmful cultural and historical myths. In a recent study by Tanner Mirrlees and Taha Ibaid, for example, ten prevalent war games that were released between 2001 and 2012 were researched and found to have negatively portrayed and played into harmful Muslim stereotypes and Islamophobia.

Meanwhile, critically acclaimed franchises, such as Medal of Honour and Call of Duty, have had criticisms of portraying World War Two as a “just war” levied against them since their release. And yet none of these controversies is explored. The exhibition ultimately only offers an extensive look into how certain games (like the Indie ones featured in Level 06-08) can contribute to informing and improving wider historical understandings. It fails to explore the harmful ramifications the most popular games may have regarding historical understanding and war memory.

Ultimately, well the ‘War Games’ exhibition may serve as an excellent introductory experience into how war remembrance and heritage are incorporated into the digital realm of video games, the ideas presented throughout the exhibition would have been more thought-provoking if expanded upon. Although the exhibition provides a few examples of games that present more nuanced portrayals of real-life conflicts, it lacks any investigation into the potential harms of the simplistic war narratives found in some of the more popular FPS games. Future exhibitions on this topic should aim to delve deeper into such debates and provide more of a balanced perspective on the cultural impact of war games. Being presented with the more difficult questions surrounding historical representations in this new digital format would significantly expand our overall understanding of the increasingly prominent role war games play in shaping war heritage.

The ‘War Games’ exhibition can be seen, free of charge, at the London Imperial War Museum until the 28th of May 2023.

Games featured at the expedition:

- Call of Duty: Modern Warfare

- Arma 3

- Sniper Elite 5

- Wolfenstein 3D

- Six Days in Fallujah

- Through the Darkest of Times

- Bury Me, My Love

- This War of Mine

- 11-11 Memories Retold

- Worms

Sources:

1.See chapters 2,6 & 7 in: W. M. Knoblauch & M. W. Kappell (2013) Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

*2. (2022),A World At Play: The Current State of the Video Game Industry: What the Video Game Industry Looks Like in 2022. Retrieved from URL:** Video Game Industry Statistics and Trends 2022 | Liquid Web.***

3.Tanner Mirrlees and Taha Ibaid. The Virtual Killing of Muslims: Digital War Games, Islamophobia, and the Global War on Terror. Islamophobia Studies Journal. 2021. Vol. 6(1):33-51. DOI: 10.13169/islastudj.6.1.0033

4. Ramsay, D. (2015). Brutal Games: “Call of Duty” and the Cultural Narrative of World War II. Cinema Journal, 54(2), 94–113. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43653093.

Christina Chester is a second-year BA(Hons) History with English student at Northeastern University London.